3. februar 2008

The role of the editor

Under siege: The need for a new Editorship By Frédéric Filloux, editor Schibsted International The new breed of editors will […]

Under siege: The need for a new Editorship

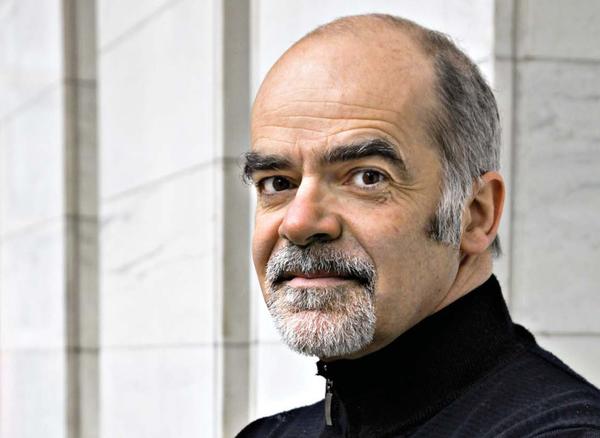

By Frédéric Filloux, editor Schibsted International

The new breed of editors will have to be cool-minded and focus on one question: what makes my editorial product unique?

Call it the tale of the editor and the blogger. Twenty years ago, the editor was a dominant figure in the news business. He was reigning on cohorts of journalists, distributing assignments, dispatching reporters, dealing with columnists, editorialists and self appointed opinion makers.

More than any other, he was epitomizing the very fabric of a news organization. At that time, budget was an abstract notion, readers were faithful and demanding.

During editorial meetings, decisions where taken with a superb ignorance of the wishes and expectations of the readership. Market research was an unknown science and even seen as a nuisance. Some newspapers remained quite inspired and stuck to their audience, others grew increasingly disconnected. But nevertheless, it was working fine that way. Here and there, newspapers and magazines were throwing huge amounts of money in lavish redesign that yielded mixed results. But general trust in the ability to deliver remained largely intact.

Glorious times, indeed. It was actually the end of it. Slowly first, readers became older, more irregular and finally eroded. Then, two waves struck: the internet and the recession.

The first one translated into a total disruption of a business model that has been here for more than a century. Along with the dematerialization of news came the free culture.

Suddenly, an entire generation became convinced that news had to be free, and in the process, the notion of trusted brand lost its appeal.

Ubiquity, instantaneous availability of news, led to a massive destruction of value: why pay for a newspaper or a magazine when they are available for free on the internet? At the other end of the spectrum, the production side was facing the symmetrical question: why maintain a staff of photographers or video journalists when the first pictures of an aircraft landing into the Hudson River hit the internet exactly 8 minutes after the accident?

Why have an expensive news bureau in Mumbai when the micro-blogging service Twitter was spitting bursts of news at a riveting pace? Fact is: breaking news became a commodity for the biggest part of it.

Enter the blogger

With two challenges the editor has to face. The blogger’s main characteristic is its lightness. Both in terms of structure – a computer in a basement for the more modest ones – and in terms of meaning. The blogger doesn’t report, he propagates whatever shows up in his sight and adds a layer of opinions of variable quality. And he does that quite fast, furthermore challenging the editor. Through a social resonance process, he amplifies a rumor, a controversy, sometimes a fact, and blows it out of proportion. Traffic will surge as relevance and accuracy will fade.

That’s for the vast majority of them. Incidentally, bloggers can be true experts, with remarkable insights; in many areas such as science or economy, bloggers are sometimes more interesting, more thoughtful than journalists.

Those two forces work mainly against the editor: both as a stimulus – the crowds expressing itself – and as an intellectual competition when sometimes a true expertise emerges from the noise. In itself, these shifts in intellectual dominance would have been sufficient to challenge the traditional way of gathering and publishing news.

In such a context, recession is acting as catalysis, shattering business models, precipitating the fall of the weakest companies. Publishers realize in horror that a reader shifting from print to the web brings only a fifth of what he used to do. Even the once glorified free model is unraveling as the advertising market is running out of steam.

There is although a more constructive – if not optimistic – view of what’s happening. The current downturn is likely to create the momentum for the catharsis our industry needs. It’s time for decisive change in the news sector. Not the kind of mending we are used to, but a true and decisive reinvention.

Hence the questions: how can we preserve the fundamentals of our trade? How can we combine the expensive thoroughness of the news gathering process with the challenges posed by a new breed of small, scattered and agile competitors? In that context, what should be the priorities for a modern editor in a major news organization?

The new game led everyone to buy the idea that the entry barrier to information was down to zero, that a couple of dedicated, self-appointed, «citizen journalists» could do better than the staff of a classic news organization. It all depends on how you define news. It works fine for the lucky shot (the plane falling into the river), it can also be true for gossips, but it doesn’t apply for the bulk of the news flow. It doesn’t apply to what makes the very fabric of journalism: context, analysis, perspective, and investigation, quest for accuracy.

The New York Times publishes more than 3000 corrections a year, Le Monde about 1000. How much for a blog, even a serious one? None. This thoroughness comes at a price. News is horrendously expensive. In today’s dollars, the Watergate investigation would cost around 2 million; to maintain a presence in Baghdad, the New York Times spends each year 3 million dollars (salaries not included); that is half of the entire revenue of the biggest pure players news sites.

Blogs, even super-blogs with dozen of journalists can do a remarkable job at following business or politics, but none of them can line-up the journalistic firepower required to cover issues that really matters in a modern democracy such as an abusive war or the misbehavior of a public administration. In a nutshell, the main role of the editor is to make its organization incomparably more relevant and trustworthy than the best blog system.

Not an easy task. It requires a small but potent team. Let’s face it: the best news organizations in the world are run by no more than half a dozen dedicated editors. Only a small group of bonded, focused people can keep the decision-making process swift and simple. In a newsroom, chain of command is always too convoluted.

The impresario

By all means, talent will remain an essential factor of difference. Spotting, nurturing, comforting talent will still be the most critical part of the job. The editor’s talent must be to foster others. Editor is the ultimate impresario of the newsroom. He or she should be the steward of the collective intellectual brainpower, way more than the public relation forefront of the company.

Managing talent does go along with a certain dose of enforcement. Let’s draw a parallel with the way Apple is managed. Its cluster of technological achievements in consumer electronics is most certainly the result of design and engineering prowess. But in the obsessive quest for perfection, Steve Jobs was the «chief enforcer», pressuring – and inspiring – a carefully assembled dream team, fighting down to the tiniest graphic detail and repeatedly sending projects back to the drawing board. Excellence doesn’t happen by accident.

Dealing with talent also involves hiring, motivating and, yes, firing people. What goes without saying in many sectors can be seen as a novelty in the news business. Too often, hiring is restrained to the mere expression of well-entrenched collective habits rather than a thorough vetting process. Journalists are usually not trained to properly interview and evaluate potential recruit.

Most of the time, those who have the ability to pick-up talent actually dig in their own pool of acquaintances, select a medium profile – good enough to satisfy their bosses, quiet enough to eliminate the risk of any creative disruption in the quiet order of the place. The byproduct of this standard procedure is the emergence of a «passable» culture induced by the no-risk approach.

In many European or American newspapers, the effect was leveling off the general competences of journalism. In the last two years, this self-protective mentality was reinforced by the economic crisis in which media groups suffered severe losses in market values and began to slash staffs. Not the best time to foster a daring culture.

It goes with newsrooms as in geology: aggregates tend to accumulate and to solidify. In the last twenty years or so, this clock-punching attitude created multiple layers of inefficiencies, long chains of command. It is not uncommon to see fifteen hierarchical levels between a top editor and a junior reporter.

The most apathetic part has always been found in the mid-management. The top management usually appoints this «soft» body – some could say «weak» – which in turns draws its legitimacy by representing the journalists who therefore become its constituents. That is the opposite of a decisive management model. In the past, editors had two excuses to this passiveness.

First, they had no, or little, management training that could have been helpful to prevent this evolution; it simply was (still is) not in the culture of media companies to prepare people when they are called for the top jobs.

The second excuse is the rigid structure imposed by years of union-led labor agreements. Of course, it varies from one country to the other. But in the vast majority of newsrooms, the current promotion system does help to reward talent. In order to keep a good reporter from being stolen by the competition (a limited risk today), this person got promoted – unfortunately with some management duties attached, he or she was not prepared to handle.

Evidently, these trends need to be reversed. It won’t be done overnight and will require decisive management overhaul: training programs; possibly a revision of the compensation system (introducing a light dose of meritocracy and performance criteria could be an idea); implementation of true human resources policies; today, HR people are too often relegated to a mere administrative role with very little input in key decisions.

However, they should work hand-to-hand with top editors and be part of the strategic thinking for companies who rely so much on intellectual power. For brutal as it its, the current crisis will force unions, syndicats, guilds to make some concession in the bargaining process and to devise better ways to reward competence.

Talking Business

There is no longer room for folklore in the news business. The era of Ben Bradlee, storming the newsroom of the Washington Post during the Watergate investigation might have inspired many young reporters, but these times are over. The twenty-first Century editor has to encompass many capacities his elders enjoyed the luxury of ignoring.

Take the business side for instance. During thirty years, up until the nineties, newspapers saw their revenue growing at a steady pace. They were only marginally affected by economic cycles. Even the 1981-1982 recession was almost painless. As the management of the Los Angeles Times suggested mild expenses restrains in its 1000 staff newsroom, Paul Steiger, one of the managing editor decided to eliminate first-class travel.

The top editor of the paper came to him, saying: «I like flying first-class. You are setting a bad example» (Steiger found symbolic cuts elsewhere). A few years later, as he became a deputy managing editor of the Wall Street Journal, Steiger heard this comment from the Dow Jones CEO about the editor Norman Pearlstine: «We gave Norm an unlimited budget and he exceeded it!» Pearstine, one of the most talented newsman of his generation, later went to the Carlyle Group, a private equity firm, where he undoubtedly learnt the arcane of budgeting (he’s now chief content at Bloomberg, one of the most performing news organization in the world).

The era of financial irresponsibility is definitely over. Today, hiring freezes yield to buyouts and now to brutal batches of layoffs. Even before that, the structure of news outlets changed radically. Colorful media barons gave way to cold-blooded shareholders who, in turn, seek reassurance by hiring MBA’s. Those are running the show now. Some are brilliant strategists, some are mediocre bean counters, wrecking the spirit of a company. Whatever their qualities, shortcomings, agenda or vision, the editor has the duty to be credible vis-à-vis his directors and managers. His first line of defense is to talk their language.

He must convince them that talent management and vision remain the unique economic value in any news organization. That goes for the reader who gets a copy of its favorite newspaper or for the visitor of a website. They all have a choice and their decision translates into a tangible economic effect. Same goes for the advertiser. Even if the advertising model is taking a severe beat, it will remain the biggest source of income for news organizations, regardless of the medium.

The protector

For the editor, dealing with the advertising is a delicate task. Because he has to deal with it. In the same way he can no longer exonerate himself from the costs side of the business, he is entitled to a decisive input in the advertising strategy. No redesign, no change in the way a newspaper, a magazine or a website is built can be engineered without taking in account the potential impact it will have on the advertising stream.

When it comes to buy some ad in a media, product is a key factor. And as the day-to-day chief architect of the product, the editor bears a clear responsibility of its attractiveness to the advertiser. This duty implies a delicate balance. On one hand, a good journalistic execution will inevitably attract advertisers. Experience always shows that advertising community rewards way more editorial quality than complacency or eagerness to please. Nothing is more flattering for a brand than being in a good editorial context. High-ranking executives, publishers/editors or advertisers usually share this view, when they are decided to look at the big picture.

But it is a different story when dealing with the foot soldiers of the trade. Whether it is the sales team of a media buying agency or the sales force within the news organization itself, they tend to share the same culture – immediate and individual profit through personal incentive – and the same vision – the ultra short term one. Powered by such mentality, advertising mutates into a corrosive, if not a corrupting force the editorial team will have to contain and sometimes to fight.

Pressure goes in two flavors: the preemptive and the retaliatory mode.

The first one usually shows up in a gentle way, in the form of undue gratification such as a press junket and/or unusual access to a top official. Internally, an advertising campaign will try to sneak into news pages (paper or electronic ones) with the clear intention to blend with the regular editorial content. (In France for example, vast segments of consumer medias, are known to be sold to advertisers). Editors will have to be vigilant by maintaining a Chinese wall between the news department and the sales team. Coming back to blogs, that is also a key factor of differentiation: bloggers have often a stretchable ethic and are more prone to be given the latest Samsung in exchange for a rave review. For a professional news organization, preserving these standards is preserving a competitive advantage over the blogging crowd.

Inevitably, the editor will have to deal with the second flavor, which is the retaliatory mode. Two anecdotes. The first one is recounted by Wired magazine. In 1970, Walter Mossberg was the Detroit correspondent for the Wall Street Journal. One day, he lands a scoop about American Motors Corporation. Asked for comments, AMC executives reacted by threatening to cancel all ads in the Journal if the story was published prior to an official announcement. The WSJ didn’t balk and, after a further checking, published the story with a bigger headline. Needless to say, this episode impregnated Walt Mossberg’s career. He would later become a quite respected personal technology writer, fiercely unbowing to the electronic industry. His column is a place of choice for advertisers.

Second anecdote

a few of years ago, Schibsted’s free newspaper 20 Minutes in Paris ran a front page piece about the dominant telecommunication player which was bleeding subscribers at an alarming rate. A rather negative coverage. Predictably, the entire ad food chain went nuts, threatening with serious retribution from the brand which was, by the way, the biggest advertiser of the paper. Funnily, the higher you climbed in the hierarchy, the lesser the anger was. Finally, the telecom group assessed the story, which was harsh, but thorough and balanced with all sides being given the opportunity to talk. End of the incident.

That leads to one conclusion: credibility, fairness, along with legitimate resistance, breeds respect. And respect brings money. And money is the fuel of journalism. More than anyone else in the management, the editor is the ultimate protector of the credibility – i.e. the economic value – of the news organization.

The storyteller

Twenty years ago, storytelling and subsequent journalistic production was pretty straightforward. The editor and his staff were planning a coverage tactic in accordance to the type of subject, deploying adequate resources – usually one or several writers – the photo desk would arrange picture gathering, either by sending someone, hiring some freelance or digging in the newswire production. All of this was constrained by a deadline once a day, a single editing process. Such a simplified sequencing is history.

Today, news is expected to be packaged, transformed, and disseminated in multiple formats and in accordance to a dynamic timeline. The notion of storytelling has been completely overhauled. The goal is to satisfy increasingly segmented audiences with different wishes and a variable attention capacity.

Let’s take a serious event such as a terrorist attack. It will be first treated as breaking news, simultaneously on the web and on a mobile site. It will require constant updates, searches for relevant sites that could have first hand material: photos, video taken from a mobile phone. At the same time, tons of email and SMS alerts will be sent. That’s just for the first hours.

In this phase, competition is expected to come from all sides: from Twitter, which will send short updates, from bloggers, all of them with a flexible relationship to accuracy (that’s not the point in this era of fact-less, perpetual, crowd-powered contribution to the newsflow). Then, as events unfold and more depth and analysis are required, multi-competences coverage will be organized: good writers and editors for the newspaper, drawing material from dispatched reporters who will also be asked to file some internet updates.

Multimedia people will collect, filter, edit their own material to feed the web beast. Animated graphic designers – usually young Flash artists dealing frantically with mouse and electronic tablet – will join the fray, working on complex data provided by specialized editors, together producing great interactive features. In the meantime, the newsroom will be deluged with audience input: factual elements, pointless shouting, or maybe some original perspectives. That public-generated content cannot be just ignored. At some point, it will deserve to be published.

The public will also ask for a better understanding on what’s going on, with backgrounds, fact sheets, relevant archives organized in the most comprehensive way. In recent years new forms of explanatory journalism emerged. Any coverage is now expected to match Wikipedia or About.com as it comes to outline complex issues.

No one escape that. Many web sites ranging from general public to specialized ones have been surprised by the click-rate of pedagogic treatments. At the same time, the digital news consumer wants to get all of the above in a compact and easy-to digest way. Remember: the reader who spent thirty minutes reading a newspaper, now devotes only a few minutes when he visits a website, hopefully several times a day.

For the editor, deploying the best tools at the appropriate time imposes to have some notions about the digital news chain. Evidently, he is not expected to understand the nuts and bolts of an interactive feature, but he must know enough to decide when it is the best moment to produce what. Mastering digital techniques is now a critical part of strategic editing in a modern media. Today, choices involve how to open content to the oustide in order to channel back readers.

The editor will have for instance to decide upon deploying new techniques of content dissemination on third party web sites. Big news organizations such as The Guardian, the BBC or the New York Times are already making their content available to anyone through sophisticated tools. This is a huge bet on the value of the brand. For a large part, such a decision will fall on the editor’s lap.

He will use market research and also «guts analysis» to assess the risk of a secondary distribution.

Today’s editor is literally under siege. He is facing the simultaneous perils of elusive and segmented audiences, the needs for management changes, technological challenges, and a scattered but aggressive competition, all in the context of the most difficult times ever seen. In such a perfect storm, the editor will have to be cool-minded and focus himself on one question: what are his weapons of choice to rise above the ambient noise?

Where lies the uniqueness of his editorial product? Answers are: excellence, relevance, and accuracy. Building an editorial strategy is the only way to avoid being outmatched by legions of crowd-pleasing amateurs.

For the editorial team, dealing with such adversity requires a wide set of qualities. The daunting task is now to coordinate in the most efficient manner – including economic wise – a vast array of competencies and techniques that didn’t exist ten years ago. Different needs call for different management approach.

The new breed of editors will rely more than ever on a knowledge acquired by training that will lead to long-term editorial strategies and swift tactical responses.

At stake is the survival on the kind of journalism that is essential in any democracy.

Frédéric Filloux is editor in Schibsted International. In 2002, he was part of the team who launched the free daily 20 Minutes which is now the most read newspaper in France. Prior to that, he spent 12 years at Liberation, successively as a business reporter, New York correspondent, editor of the multimedia section, manager of online operations, and, finally, editor of the paper. He lives in Paris.